Indice dei contenuti

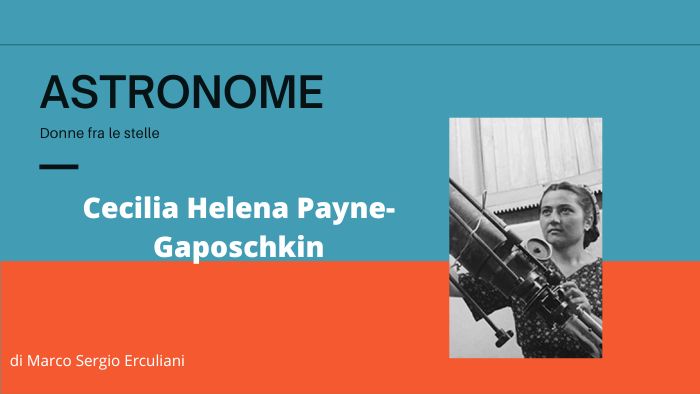

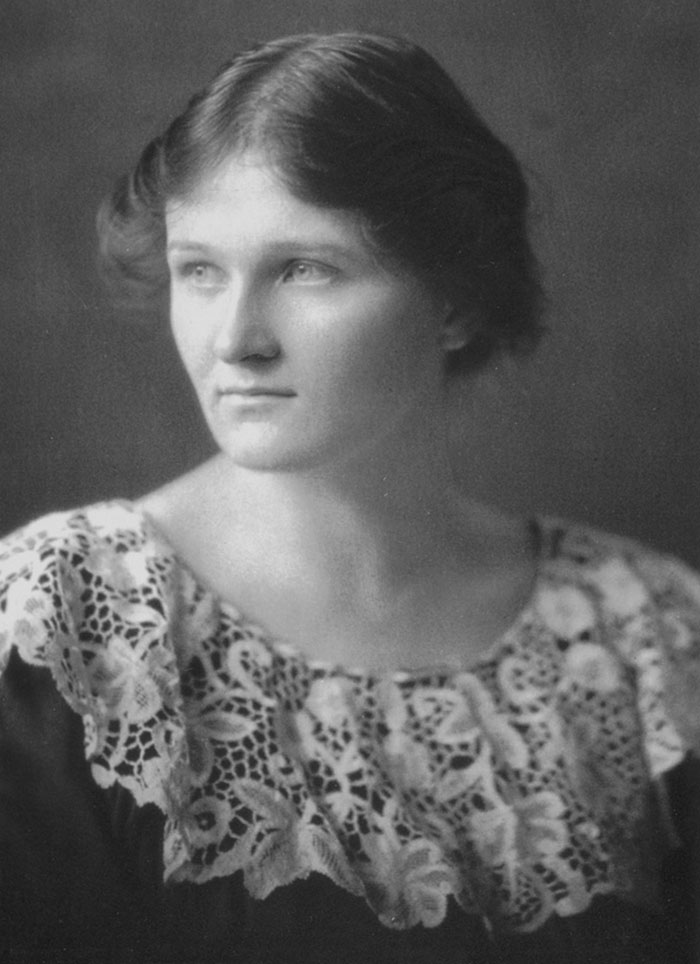

Cecilia Helena Payne-Gaposchkin

Capita, sulla Terra, che, ogni tanto, nel corso della storia, cadano delle gocce di luce dalle stelle immense del firmamento. Queste gocce di luce brillano in mezzo alla folla di luce propria, come candele in una notte oscura. Queste gocce di luce sono persone speciali, che, ognuna a suo modo, possiede una virtù che la rende unica.

Oggi vi parlo di una di queste gocce di luce: Cecilia Helena Payne-Gaposchkin. Nacque a Wendover, a pochi chilometri da Londra, proprio nell’anno 1900. Orfana di padre in tenera età, viene allevata dalla madre assieme ai suoi due fratelli. Comincia sin da subito a manifestare una intelligenza curiosa, imparando prima dei dieci anni il francese, il tedesco e il latino. Quando ha 12 anni, si trasferisce a Londra, dove inizia a frequentare il St.Mary’s College, una scuola religiosa. Come spesso accade alle menti frizzanti, non trovando molti stimoli, decide di inventare da sé i suoi interessi, che la spingono a lambire le coste della scienza. E lo fa cominciando proprio dalle basi: i Principia di Newton. Accortisi dell’intelligenza non comune di Cecilia, una nuova insegnante di scienze le dà in prestito alcuni libri di fisica e la porta a visitare i musei londinesi. Parallelamente alla scienza, Cecilia, coltiva la musica, entrando a far parte dell’orchestra della St. Paul Girls’ School.

Grazie alle sue spiccate doti scientifiche, nel 1919 vince una borsa di studio che le permette di entrare al Newnham College, il college femminile dell’Università di Cambridge, dove Cecilia completa la sua preparazione arricchendo il suo scibile con la chimica e la botanica. In quel tempo e prima del 1948, a Cambridge alle studentesse non veniva riconosciuta la laurea al termine del loro percorso di studi, come accadeva per i colleghi uomini.

Lo stesso anno, Cecilia resta folgorata dalla conferenza di Sir Arthur Eddington, durante la quale l’illustre astrofisico britannico presentava i risultati delle misurazioni effettuate durante un’eclissi di Sole nell’isola di Príncipe, al largo delle coste occidentali dell’Africa, che confermano la validità della teoria della relatività generale di Albert Einstein.

Qui Cecilia capisce che la sua strada è disegnata: deve essere astrofisica. Per questo motivo, completa i suoi studi nel 1922, ma, ancora una volta, nel Regno Unito, per una donna era impossibile proseguire gli studi con un dottorato di ricerca. Ma la sua passione la porta a seguire una lezione sull’Universo del professor Harlow Shapley, l’allora direttore dell’Osservatorio di Harvard, e, parlando con lui, Shapley la convince a proseguire gli studi con lui negli Stati Uniti, dove approda l’anno successivo.

Nel 1925 consegue il dottorato di ricerca, la prima donna ad Harvard ad ottenerlo, con una tesi intitolata “Atmosfere stellari”. In questo lavoro, applicando metodi di analisi innovativi che aveva approfondito da sola, Cecilia era riuscita a calcolare l’abbondanza degli elementi chimici delle stelle attraverso l’osservazione del loro spettro. Questo era un passo importante per l’astronomia perché dimostrava che le stelle sono fatte principalmente da idrogeno ed elio a differenza della credenza dell’epoca che le riteneva costituite da atomi pesanti come alluminio, ferro o silicio, come quelli presenti nella crosta terreste.

Poteva una donna, poco più che ventenne, rivoluzionare il mondo della chimica stellare? Certo che no! Per questo, il professor Henry Norris Russell, quello diagramma Hertzsprung-Russell, la convinse a rivedere le conclusioni del lavoro che, successivamente, pubblicò a suo nome nel 1929, citando Cecilia Payne solo marginalmente.

Dopo il dottorato, Cecilia lavorò come assistente di Shapley, accettando un impiego sottopagato rispetto ai colleghi uomini e soltanto anni riuscì ad ottenere il ruolo ed il titolo di astronomo da parte dell’accademia.

Nel 1934 Cecilia sposò l’astronomo Sergei Gaposchkin, che aveva aiutato a fuggire dalla Germania nazista, cambiò il suo cognome in Payne Gaposchkin e, con lui ebbe tre figli: Edward, Katherine e Peter.

Solo nel 1956, Cecilia divenne ufficialmente professoressa ad Harvard e Direttore del Dipartimento di Astronomia, la prima donna a ricoprire un ruolo così importante nella rinomata università americana, dove resterà in carica fino al 1965, anno del suo ritiro.

Nel 1976 le fu assegnato il prestigioso premio “Henry Norris Russell”, il più alto riconoscimento della Società Astronomica Americana. In quell’occasione dichiarò: “La vera ricompensa per un giovane scienziato è l’emozione che prova nell’essere la prima persona nella storia del mondo a vedere o capire qualcosa di nuovo. Niente può essere paragonato a questa esperienza”.

La sua intelligenza e la sua curiosità la spinse a ricevere diverse medaglie, premi e riconoscimenti. Nel capitolo 22 della sua autobiografia, capitolo che si intitola “Sull’essere una donna”, Cecilia scrisse: “Essere una donna è stato un grande svantaggio. È un racconto di salari bassi, mancanza di status, progressione lenta. Ma ho raggiunto vette che non avrei mai osato immaginare 50 anni fa, neanche nei miei sogni. È stato un caso di sopravvivenza, di persistenza accanita. […] I giovani, e specialmente le giovani donne, spesso mi chiedono un consiglio. Eccolo, valeat quantum. Non intraprendete una carriera scientifica alla ricerca di fama o di soldi. Ci sono modi più semplici ed efficaci per questo. Intraprendete [una carriera scientifica] solo se null’altro vi può soddisfare, perché probabilmente non riceverete null’altro in cambio. Il vostro premio sarà l’ampliarsi dell’orizzonte durante la scalata. E se raggiungerete questa ricompensa, non chiederete altro”.

English Version

Cecilia Helena Payne-Gaposchkin

It happens, on Earth, that, every now and then, throughout history, drops of light fall from the immense stars of the firmament. These drops of light shine in the crowd of their own light, like candles on a dark night. These drops of light are special people, who, each in their own way, possess a virtue that makes it unique.

Today I tell you about one of these drops of light: Cecilia Helena Payne-Gaposchkin. He was born in Wendover, a few kilometers from London, in the year 1900. Orphaned by her father at an early age, she was raised by her mother together with her two brothers. He immediately began to manifest a curious intelligence, learning before the age of ten French, German and Latin. When he was 12 years old, he moved to London, where he began attending St. Mary’s College, a religious school. As often happens to sparkling minds, not finding many stimuli, she decides to invent her own interests, which push her to lap the shores of science. And it does so starting with the basics: Newton’s Principia. Aware of Cecilia’s uncommon intelligence, a new science teacher lends her some physics books and takes her to visit London’s museums. Parallel to science, Celilia cultivates music, joining the orchestra of St. Paul Girls’ School.

Thanks to her strong scientific skills, in1919 she won a scholarship that allowed her to enter Newnham College, the women’s college of the University of Cambridge, where Cecilia completed her preparation enriching her knowledge with chemistry and botany. At that time and before 1948, in Cambridge the students were not recognized as graduating at the end of their studies, as was the case for their male colleagues.

The same year, Cecilia was struck by Sir Arthur Eddington’s lecture, during which the illustrious British astrophysicist presented the results of measurements made during an eclipse of the Sun on the island of Príncipe, off the western coast of Africa, which confirm the validity of Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

Here Cecilia understands that her path is drawn: she must be an astrophysical. For this reason, she completed her studies in 1922, but, again, in the United Kingdom, it was impossible for a woman to continue her studies with a PhD. But her passion led her to follow a lecture on the Universe by Professor Harlow Shapley, the then director of the Harvard Observatory, and, talking to him, Shapley convinced her to continue her studies with him in the United States, where she landed the following year.

In 1925 she obtained her Ph.D., the first woman at Harvard to obtain it, with a thesis entitled “Stellar Atmospheres”. In this work, by applying innovative methods of analysis which she had explored on her own, Cecilia had succeeded in calculating the abundance of the chemical elements of stars by observing their spectrum. This was an important step for astronomy because it shows that stars are mainly made of hydrogen and helium unlike the belief of the time that they consisted of heavy atoms such as aluminum, iron or silicon, such as those present in the earth’s crust.

Could a woman, in her early twenties, revolutionize the world of stellar chemistry? Of course not! For this, Professor Henry Norris Russell, that Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, convinced her to revise the conclusions of the work that, subsequently, he published in his name in 1929, citing Cecilia Payne only marginally.

After her doctorate, Cecilia worked as Shapley’s assistant, accepting an underpaid job compared to her male colleagues and over the years she managed to obtain the role and title of astronomer from the academy.

In 1934 Cecilia married the astronomer Sergei Gaposchkin, who had helped escape Nazi Germany, changed her surname to Payne Gaposchkin and, with him, had three children: Edward, Katherine and Peter.

Only in 1956, Cecilia officially became a professor at Harvard and Director of the Department of Astronomy, the first woman to hold such an important role in the renowned American university, where she remained in office until 1965, the year of her retirement.

In 1976 she was awarded the prestigious Henry Norris Russell Award, the highest award of the American Astronomical Society. On that occasion he declared: “The real reward for a young scientist is the emotion he feels in being the first person in the history of the world to see or understand something new. Nothing can compare to this experience.”

Her intelligence and curiosity led her to receive several medals, awards and recognitions. In chapter 22 of her autobiography, a chapter entitled “On Being a Woman,” Cecilia wrote: “Being a woman was a great disadvantage. It’s a tale of low wages, lack of status, slow progression. But I have reached heights that I would never have dared to imagine 50 years ago, not even in my dreams. It was a case of survival, of relentless persistence. […] Young people, and especially young women, often ask me for advice. Here it is, valeat quantum. Do not embark on a scientific career in search of fame or money. There are simpler and more effective ways for this. Undertake [a scientific career] only if nothing else can satisfy you, because you probably won’t receive anything else in return. Your reward will be the widening of the horizon during the climb. And if you achieve this reward, you will not ask for anything else.”

E’ in distribuzione Coelum Astronomia n°260 di febbraio/marzo 2023

oppure

PROMO ABBONATI A TUTTO COELUM!

Abbonati o rinnova l’abbonamento alla versione cartacea e..

ottieni subito l’accesso a

Coelum Digitale e Coelum Voice

un unico abbonamento per accedere a tutto e in più…. porte aperte alla Community per scambiare commenti feedback ed inserire immagini in PhotoCoelum

- Coelum Cartaceo n°6 uscite dal 261 al 266 di febbraio/marzo 2024 (ben 12 pagine in più!)

- Coelum versione Digitale consultabile su ogni device (sono disponibili alla lettura tutti i numeri dal 2022 in poi)

- il nuovissimo Coelum Voice! Gli articoli pubblicati su Coelum in podcast, per approfondire in ogni momento libero!

- Accesso livello QUASAR alla Community

Valore complessivo dei servizi euro 113,34 – prezzo speciale offerta 63,00 euro*

sconto 44%

*più spese di spedizione in base alla modalità scelta

Offerta valida fino al 28 febbraio 2023